Itinerary of Literature and Academic Knowledge

Itinerary of Literature and Academic Knowledge

Itinerary includes

Camilla Battista da Varano

Caterina de Vigri

Fra Giovanni Bertoldi

Description

The scholar first retraces the history of the problematic relationship of women with writing by reviewing some graphic testimonies of women writers-copyists, both religious and secular, between the 8th and 15th centuries.

In this context the graphic and cultural experience of Blessed Camilla Battista da Varano, educated in grammar and rhetoric like the other women of the Varano family, acquires a special meaning, since it combines the intellectual stimuli of Humanism with the spiritual experience of the Franciscan Observance. Therefore, starting from the examination of Camilla’s writings (the Transito del Beato Pietro da Mogliano [1491], the Memoria on the Olivetan monk Antonio da Segovia [1492] and a letter addressed to her brother-in-law Muzio Colonna in 1515), Ms Giovè frames the writing of Camilla Battista da Varano in the context of the wide range of graphic examples from the 15th century, seeing it as an “interesting compromise” between simple publishing, Antigua calligraphy and some stylistic expressions of humanistic lower case. After a detailed analysis of the morphology of the individual letters in the writings, the scholar dwells on the structure of the manuscript containing the Transit (the “Ferretti-Brocco” Municipal Library in Mogliano), a manuscript in which the model of the ‘women’s libretto’ and that of the ‘Franciscan codex’ are superimposed on either side. Finally, da Varano’s experience is related to that of other religious women who were active in the 15th century, such as the Poor Clares of Monteluce in Perugia and Santa Lucia di Foligno or Illuminata Bembo and, above all, Caterina Vigri, who was able, like Battista da Varano, to represent her own spiritual world autonomously through writing.

Caterina Vigri is one of a number of Poor Clares linked to the Franciscan Observance, characterized for having created a synthesis between holiness and love for culture, for example, Cecilia Copoli from Perugia, Eustochia Calafato from Messina and Camilla Battista da Varano from Camerino. In addition to illuminating codes and her own works, Caterina de Vigri painted various religious subjects, kept in the Sanctuary of the Corpus Christi Monastery. One of her paintings, depicting Saint Ursula with her companions, and Saint Catherine kneeling in front of them, is in the National Picture Gallery in Venice.

The life and work of Caterina Vigri (1413-1463) are full of interest for those who wish to get close to a model that stands out for its holiness, with teachings in the search for evangelical perfection that could easily be applied to modern times. Often remembered for her incorrupt body, placed for five centuries in a seated position in the church of the Corpus Domini monastery in Bologna, founded by the Saint herself, Vigri was a very multifaceted figure who left us, in addition to her example, important mystical writings. Above all, the famous Treaty of the Seven Spiritual Weapons, an interesting text to train for religious life.

In 2018 the remains of an ancient Franciscan monastery at Oxford University were discovered by archaeologists. For the first time in many centuries, archaeologists were able to see substantial parts of one of the university’s largest medieval teaching institutions, a convent founded by Franciscan friars in 1224, which turned out to be of fundamental importance in the history of Oxford University.

Together with their rivals, the Dominicans, the Franciscans were a major force in the transformation of the institution, focusing on more intellectually rigorous and challenging subjects in the curriculum. Although the university had already existed for some decades, it had specialized in teaching professionally-oriented practical courses such as letter writing, Latin grammar, rhetoric, basic mathematics and practical law. However, the Franciscans and Dominicans introduced a new emphasis on theology into the curriculum, which in turn led to the teaching of advanced philosophy, physics, natural history, geology and even ophthalmology. At that point, theology was considered the most modern intellectual discipline; it was even nicknamed “the Queen of Sciences”.

The friars used theology and the content of the Bible to access all those other disciplines. Thanks to the contribution of those medieval friars, Oxford rapidly evolved into the international centre of study that it is today. Archaeological research is now revealing the life of Oxford during that historically crucial transition, and it is also important because the Franciscan monastery (known as Greyfriars) was home to some of the most important scholars in the history of Oxford University and, indeed, the wider history of European academic life. Among the eminent mediaeval scholars who taught at Greyfriars were Roberto Grossatesta (one of the first great mathematicians and physicists in mediaeval Europe), Roger Bacon (philosopher, linguist and the pioneer of empirical science), Haymo of Faversham (an important international diplomat who taught in Paris, Tours, Bologna, Padua and Oxford), John of Peckham (who later became Archbishop of Canterbury), Peter Phillarges (an Italian Franciscan widely recognized as Pope at the beginning of the 14th century) and William of Ockham (an important philosopher and radical political theorist). These ‘super friars’ with a strong international reputation had the ear of kings and popes and put Oxford firmly on the international map. They, together with their ‘student hall’ and their Oxford convent (Greyfriars) were very influential in political terms and this in turn helped to give the university even greater status, attracting more and more teachers and the best students.

Particular mention should also be made of the important role of the mediaeval and late mediaeval Franciscan School in the development of ideas that would be central to laying the foundations of economic theory. In particular, the sources of Franciscan thought and the most representative authors of the 13th and 14th centuries proposed a path from the ancient conception of usury to new and significant concepts for the economy on the threshold of the Modern Age.

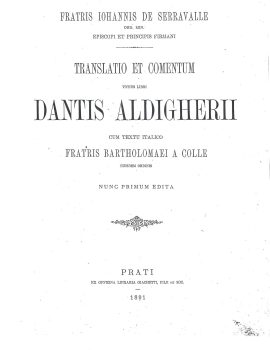

Friar Giovanni Bertoldi, born in Castello di Serravalle (San Marino) in 1350, and was Bishop of Fermo and Fano. He is famous because he translated the Divina Commedia in latin (international language in that times).